The Independent, 11 October 2003

Carl Fontana Outstanding jazz trombonist

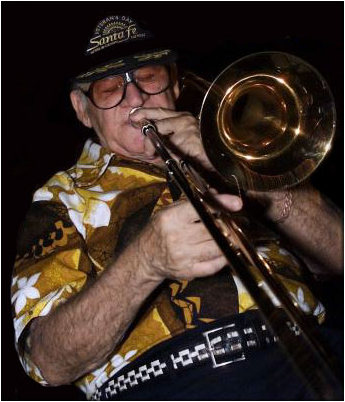

Charles Carl Fontana, trombonist and bandleader: born Monroe, Louisiana 18 July 1928; married (two sons, one daughter); died Las Vegas 9 October 2003.

It is an odd fact that all the really outstanding jazz trombonists were very low on ego. Carl Fontana, perhaps the most gifted player of his time, certainly was. He played potent and dazzling music in such a facile way that it was rather like Leonardo da Vinci sawing off a length of picture on demand.

Fontana first surfaced in 1951. The Woody Herman band was playing at the Blue Room in New Orleans when its virtuoso trombone soloist Urbie Green had to return to New York for three weeks when his wife gave birth. A young local musician hired as a temporary replacement arrived in the band room. "Can I help you?" asked the tenor player Dick Hafer. "I'm here to replace Urbie Green," said Fontana. "You're here to replace Urbie Green?" repeated Hafer, as the band musicians roared with sardonic laughter.

In performance an hour or so later, their jaws dropped as Fontana ripped off a series of agile and eloquent solos that instantly announced him as a challenger to the crown of Jay Jay Johnson, the trombonist who dominated the era. From then on, Fontana never looked back and no one has ever challenged his supremacy. His several disciples approached his speed and technical agility, but no one ever matched his sublime streams of improvisation.

Herman was so impressed that when Urbie Green returned he kept Fontana in the band. The young man abandoned his studies for his master's degree and toured with Herman for the next two years.

One day when Fontana was a child, his father, Collie, had walked into the house and placed a box in front of his son. "What's that?" asked Carl. "It's what you're going to play," his father told him, opening up the trombone case. The Fontanas lived in Monroe, Louisiana during the Depression (Carl was born there in 1928) and Collie supported his family by working as a plumber and by playing violin and saxophone in a band he inherited from another leader.

His son joined the band and worked in it throughout his high school days as well as playing in the school concert orchestra. Fontana was always an athletic man and his first loves as a boy had been football, basketball and baseball. "Dad and I had a few run-ins about whether I was supposed to be playing music jobs on the weekends or playing ball in some tournament or other. He won all the arguments."

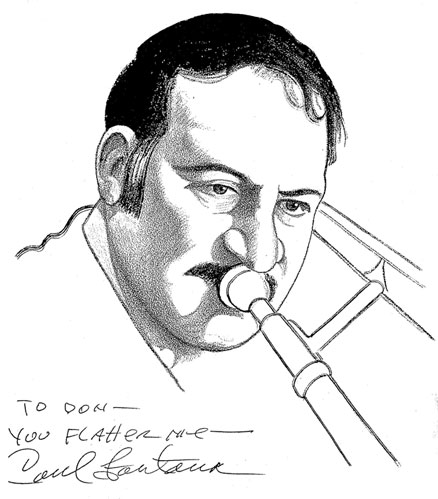

A big man of imposing stature, Fontana was a benign and amusing companion when I interviewed him in Florida some years ago, but he could be intimidating when he felt like it. Many years ago, one of the sidemen in one of the big bands had been making unwanted suggestions to some of the other musicians' wives. Fontana approached him and spoke cordially. "You're leaving this band," he said. "Whether you go out vertically or horizontally is up to you."

Fontana was awarded a degree in musical education at Louisiana State University in 1950 where he also played in concert and symphony orchestras. By the time he joined Herman the following year he had developed the unique way of combining a plump tone with the fast-tonguing of notes that caused a re-thinking of trombone techniques the world over.

His two years with Herman gave Fontana a love for the big bands that never left him, and because he was such a proficient sideman and a good reader for a time his talent was buried in the ranks of the Lionel Hampton and Hal McKintyre bands.

But in 1955 he joined the band of Stan Kenton. Kenton was under no illusions about Fontana's talents and brought him right out front as one of the band's major soloists. Kenton's band had earlier been something of a pretentious monolith but by the time that Fontana joined it had been considerably loosened up by soloists like Zoot Sims and Lee Konitz and, more importantly, by the arranger-composers Bill Holman, Gerry Mulligan and Gene Roland.

Deployed against the ranks of powerhouse brass, Fontana's solos were breath-taking. He was featured on the perennial "Intermission Riff" but more importantly Holman wrote two specific features for him. The first was the fluent assault course for trombone called simply "Carl", whilst the second was a setting of "Polka Dots and Moonbeams", which exemplified Collie Fontana's advice to his son: "Whenever you play a ballad, play it as if you were talking to your best girl."

Although Fontana had startled trombonists throughout the world, it was only when Kenton featured him on his 1956 tour of Europe that he conquered the general public. His modest manner at the microphone (Kenton let him introduce his own features) belied the pyrotechnics that followed and delighted audiences across the continent - but not in Britain where a ludicrous Ministry of Works ban still prevented American musicians playing here. British fans showed their devotion by taking the boat to Dublin where the Kenton galaxy was on glorious display.

An ex-Kenton trombonist who had made an even bigger name for himself, Kai Winding, was able to tempt Fontana with money to join his band, which consisted of four trombones and a rhythm section. Then in December 1957, before moving to Las Vegas, he deputised for Bill Harris in the Woody Herman band.

Las Vegas became Fontana's base, and he worked contentedly in mundane show bands there, leaving when called on to dazzle the rest of the world as a jazz soloist. In 1966 he toured the world on a US State Department tour with the Herman band, coming to London before touring in Africa for 12 weeks.

From then onwards he was called regularly to festivals, tours and the newly emergent jazz parties to grace their all-star line-ups. He worked with Benny Goodman in Las Vegas in the mid-Sixties and became a key member of Supersax, a band devoted to re-creating the solos of Charlie Parker, in 1973. He was in the various bands that led eventually to the emergence of the World's Greatest Jazz Band in 1975. Here he showed his abilities to play convincingly in such Dixieland surroundings. "I'm just an old bebopper at heart," he had told me in Florida.

Fontana co-led a group with the drummer Jake Hanna that recorded and appeared at festivals in 1975 and later toured Japan. Unusually, although he had appeared on so many recordings under other leaders, Fontana didn't make an album under his own name until 1985, when he led a quintet that included his long-time friend and musical associate Al Cohn.

He had more good exposure when, during the Eighties, he appeared regularly on the National Public Radio show Monday Night Jazz. By the Nineties he had retired from regular work in Las Vegas and only toured as a jazz soloist. At this time he came to London to play at Ronnie Scott's in tandem with one of his disciples, Bill Watrous.

In Las Vegas he continued to play for fun in a quintet that he co-led with the tenor player Bill Trujillo. One night, at the end of the evening, he turned to Trujillo and said "You'll have to take me home. I can't remember where I live." It was the onset of the Alzheimer's disease that was to lead to his death.

Steve Voce

|